My awe of living and working in a coastal National Park lasted about two weeks. My romanticization of this new life was the only thing that would keep me going.

This post has been in the works a long time because every time I sit down to write, I get so pissed off that I have to log out and go calm down.

TLDR:

- pay discrepancy

- fucking QUICKSAND

- using personal vehicles for field work-- we spent 2-4 hours on the road each day

- long, inconsistent hours-- we had to work around the tides, which meant very late nights, very early mornings, working weekends and holidays, and absolutely no routine

- absent supervisor with unclear expectations

- type B manager who could not keep her own ducks in a row, much less other people's

- not being told we were to present our research until 10 days before the presentation

I'm not trying to ruin anyone's life, so I'm not mentioning real names or places. I'm just being honest about my internship from hell on my personal blog.

My first red flag should have been that the job didn't pay as much as it advertised. When applying to positions, I kept an Excel spreadsheet of all the information about each posting, including the pay. This one advertised that it paid $600/week with free housing. It was a step up from the job I had at the time, which paid $500/week with free housing. However, as I filled out my hiring paperwork, I saw that it listed my salary as $480/week (before taxes.) I went back and checked my Excel sheet-- $600, as I thought. Maybe I had written it down wrong? I was so sure. I went back to check the job posting-- it was gone. There was no way to check. I didn't want to make things awkward with my new boss by asking for more money (I should have.) I had already turned down all the other positions I'd applied to, and unless I wanted to move back into my parents' house, I didn't have a choice but to continue my onboarding paperwork.

My Ameri Corp$ counterpart and I later learned all the other techs, who did (easier) more general work and had a 6 month term instead of a 3 month, were making $720/week plus free housing. 🙃

Week 1 was a dream. I'd requested to start a week earlier than the others because of when I had to be back in WV for grad school. Since the other techs weren't there yet, there wasn't much for me to do. I tagged along on other projects, met other employees, and started writing a page for the website about my research project. It was all slow and peaceful. I decided to start vlogging on TikTok for my small audience of family to see what I was up to.

Week 2 was all orientation for the other new techs. I already knew most of the stuff from immersion the week before. We got CPR and Wilderness First Aid certifications and visited our field sites for the first time. Most of the others were fresh out of undergrad and didn't know much about field work. For once, as they asked me for advice, I felt strong and capable and like I knew my shit.

There were 15 of us early career girls: two science communication interns, two year-long fellows, four six-month ecology techs, two three-month Ameri Corp$ (me & J), a 3-month undergrad intern, and four summit restoration techs. None were men-- we had several conversations about the leaky pipeline theory. There were two permanent scientists, H and Bird Man. Bird Man worked exclusively with birds and one of the fellows. All the other projects fell under H, who was finishing her PhD. To help H's work load, there was a manager for all the early career peeps, S.

I received a lot of Google calendar invites that week, and was told more details for everything were coming. One called "Presentations" (no description) was scheduled the last week of my term. I accepted it and thought nothing of it, assuming we would get more details later.

The physical copies of my first published poems arrived that week. It was a good time.

Week 3: My field partner, J, and I were to spend the summer surveying marine worms around the park. We were to learn how to do this with the help of a local worm harvester whose family has been doing this for generations. Frank was a wonderful, 70-something gentleman who called us "dears" in his Maritime accent, but he had no earthly clue how a cell phone worked. I tried fruitlessly those first two weeks to get a hold of him. He must have assumed my West Virginia number was a spam caller, because he never answered my calls or texts, and I'd bet money my introductory emails are still sitting unopened in his inbox with hundreds of thousands of others. He only responded to our supervisor's messages.

So H sent him an email saying her techs would set up a time to go out worming with him sometime that week. She gave him our numbers and emails. He responded with enthusiasm.

"Hey Frank! We're planning to go to the Thompson Island good site on Wednesday. Could you meet us there at low tide?" No response to that, in email, call, or text. H emailed him herself, and Frank agreed to go out with us. But it was set to storm on Wednesday, and Frank didn't respond to any of our attempts to confirm he still wanted to go out. "Maybe he'll just meet us there?"

Frank was not there when we pulled up. We decided to try calling him from J's phone, since her D.C. number was closer to Maine's area code than my West Virginia one. For the first time, he picked up for us. "Hello?"

"We're out at Thompson Island, Frank-- are you still planning to meet us?"

"No, dear, chance o' storming today." Frank pronounces dear "dee-uh" in his gravelly, thick Boston accent. He was loud enough without speakerphone. "I didn't hear from you, so I didn't plan on going out." J and I side-eyed each other.

"We're sorry about that, we've been trying to reach you. Would you be able to call us later today when we get back to $ch00dic so we can set up another time?"

"I can't. I don't have your number, dear." More side-eye. He was talking to us with her number right now. "Well you girls be safe. If you hear thunder, get the hell out. You're sitting ducks out there with that big metal worm hoe."

H had sworn to us that there was no quicksand at the sites we went to alone before meeting Frank. When we finally had a sit-down meeting with the four of us, he corrected her. There were, in fact, "honey pots" in every mudflat, and we could have found one with a foot in the wrong place. Wonderful. I love undisclosed danger.

Weeks 4-6: The reality of my situation set in. If not for the friendship of my new roommates and coworkers, I don't know that I would have made it to August.

There is no set schedule when you work in the mudflats. These barren expanses are underwater except for a small window at low tide, which happens twice a day roughly 12 hours apart. The tides are on a 12.5 hour cycle, so low tide might be at 3am and 3pm one Monday, then 4am and 4pm the next, and so on. The following Monday, low tides will be at 10am and 10pm. It's not safe to be out on the flats in the dark, so really only one low tide a day was an option. This meant we alternated each week either having very early mornings or very late nights, and each day, we started an hour later than before. I could not have a routine.

It also took a shit ton of prep and cleanup work to go out in the field. Every day, we had to put down a tarp in the vehicle and load our equipment, then drive two hours to our main site on MDI. Mudflat mud is incredibly destructive: it wears down everything it touches and taints everything with a permanent murky smell. Frank taught us to rinse everything in salt water as best we could before leaving a site, just like the wormers, so our equipment would last longer. On the way back, we would have to stop at the only place that sells propane to have a certified Propane Pumper refill the propane-fueled field van. After our two hour drive back to headquarters, we had to rinse off the salt water with fresh water so that wouldn't wear things down and hang it all out to dry until the next day.

Nothing air dries on the eternally foggy $ch00dic peninsula. It's like living on the Twilight set. Water got into our hip waders the first week, and we had damp feet for the next three months.

The car situation itself was a nightmare. $ch00dic had 15 interns that summer, most working in pairs in places that required driving, but only two field vehicles. (They would acquire one more halfway through the season, but Team Mud wasn't allowed to use it because it was the only $ch00dic vehicle that didn't smell like mud yet.) And those two cars? A propane-fueled 16-passenger van and a 2002 Nissan with no automatic locks, no AC, manual crank windows, no aux input, and this fun little feature where when you turned the headlights on, the dash lights went out. This created an interesting dilemma when driving in the dark or the rain: you could either see where you were going or know how fast you were going on the giant speed trap that is the only road to the main park Island. We usually took the van, as we were an NPS-funded project as opposed to a $ch00dic-funded project, unless it was an EarthWatch week and the van was needed to transport teams of volunteers.

On the way back from doing a photoshoot in the mudflats with us in July, the communication intern would learn the hard way that the Nissan's registration was expired. It had been expired for over a month when she got pulled over-- the responsibility of S.

S is a self-described Type B person, which is not a trait that the sole contact point for 14 early career professionals should have. She is the most disorganized person I have ever met and seems to think it is a fun quirk, not a devastating flaw. I like her as a person-- she's good at crafts and into nature, she goes on adventures in her Subaru Outback on the regular, and has several cats-- but as far as managing people goes, I would prefer to be overseen by a rabid chimpanzee.

S forgot to tell her employees things regularly: that the only available field vehicle was in the shop and we would need to take our personal cars, that the work schedule had changed, that a flight of volunteers was now coming at a different time, that we weren't allowed to let the volunteers stop and have ice cream they paid for with their own money, that we needed to tell the kitchen to prep packed lunches for 12 volunteers unexpectedly. But the one I haven't forgiven her for yet was forgetting to tell me that I would be giving a presentation on my project.

We were all worked up about S and her management style, so to de-stress, the roomies and I went to Art in the Park in a nearby town on Saturday of Week 6:

Week 7:

H was busy. We went an entire month without hearing from her (which is crazy for a 3-month internship.) There were all kinds of questions we needed to ask her about study designs, but we couldn't reach her. She was too busy with her PhD and the many projects she had going on in the park. She made me appreciate how wonderful Pam and Dawn had been.

I've learned what kind of mentor I don't want to be like.

Frank seemed disappointed by her lack of involvement, too. I think he had doubts that our project would amount to anything given our little experience and mudflat knowledge-- and rightly so. We went out on the flats with him twice. It was just me and J and the smell of mud for over two months.

We worked through July 4th because of the moon phase. We were on the wrong side of the island to even see fireworks from where we were surveying.

Week 8:

Week 9:

Part of my quest to visit every part of Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge was a long drive inland. I got to my destination through Google Maps with no trouble, but when I put in the address to go home, it was as if the route I'd taken no longer existed. It only showed a new route twisting and turning in the opposite direction from the way I had come in. I shrugged and trundled down the gravel road in my little Kia Rondo.

It could have ended very badly. The road went for miles without passing a single building, getting rougher and narrower. I passed men in army uniforms practicing driving those massive military trucks. The only other people I saw were the occasional grizzled men driving lifted trucks, who looked at me quizzically in my overalls and pigtails in a fishbowl car in the middle of nowhere while my speakers blasted "King" by Florence & the Machine on repeat. I got dangerously low on gas and was starting to panic. Just as I thought my car couldn't possibly clear the rocks jutting up out of the road, I exited through a thin clearing in the pines and was back on a paved road near farms. I made it unscathed, and brought home wildflowers for our kitchen table.

Week 10:

Week 11: I detoured to Canada. The original plan had been to go to Prince Edward Island and have the Anne of Green Gables weekend of my dreams just before heading home. This plan was shattered by S telling me that Google Calendar invite I had received months before was for my own talk on my mudflat project TEN DAYS before said talk was supposed to take place. J was also to give her own separate talk-- even though we had done everything together-- and so were the science communication interns. We were all flabbergasted. There was no way I could go through my data and put together my talk in time unless I worked on it over my PEI weekend, so I gave up the trip. I was furious.

Instead, I took a day trip to the closest Canadian island.

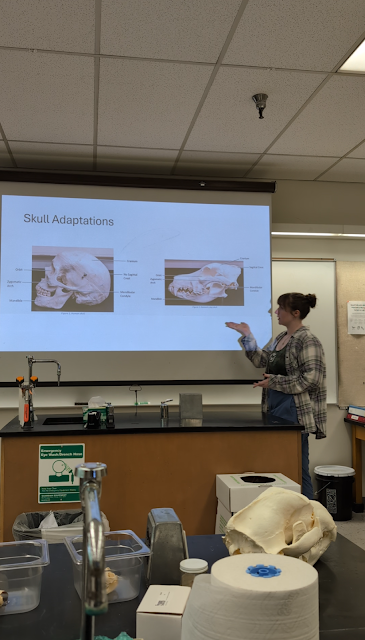

I gave my practice presentation that Wednesday. H attended and had a lot to say-- bold words from someone I had barely seen all summer.

"First of all, I just want to say I felt very rushed listening to you speak. I need you to take a breath and just slow down." I always talk at that rate. I'm just a fast talker. If she had spent any time with me that summer, she would know that-- but she hadn't been around. She proceeded to pick apart our study design and the way we had defined things, the very things we had questions about early on but couldn't reach her to ask about.

The only things she seemed to like was the quick video I had put together to show our methods.

We gave our presentations on Friday. My methods video would not play.

I was livid with S-- she was so disorganized. Why hadn't we had our practice presentations in this room so we could practice with the same equipment? I know it was open then. I could have troubleshot then, and now I had risked my phone in the mudflats and wasted time going through clips for nothing.

Week 12:

H did acknowledge that her mudflat crew tended towards burnout each season, so she offered us a second project to work on: eelgrass monitoring. It was a blessed relief to hike to tide pool sites and step in the ocean to count aquatic plants. I was delighted by the hermit crabs at the sites.

I enjoyed learning from an old timer like Frank and leading citizen scientist volunteers. I made great friends from all over the country. I was inspired by Zoe and learned to adventure by myself. I learned I can deal with anything for three months. I don't know that I gained good references-- I was incredibly blunt in my exit surveys. Overall, Maine was an adventure, and it was (kind of if you ignore the hellish work conditions) fun to dabble in marine biology, but I knew I belonged in the forests and creeks of Appalachia.

On my last day, I got a coffee from the Downeaster and took it out to a cove my roommate told me was a good place to see seals. The roomies helped me pack up my car, and I was back to the hills where I belonged.

"Do you want a cookie?" For making it through my internship from hell?? Absolutely.